Everyone wants a piece of Pharrell these days, and somehow he finds enough to go around… on that day it was Hans Zimmer, Mayer Hawthorne, and Wiz Khalifa.

HER: Spike Jonze and Humberto Leon Interview, WSJ

Matthew Goode

British actor Matthew Goode talks about country living and why he hates method acting…

Truffle Dogs

TEACHING OLD DOGS NEW TRICKS, a tale of culinary canines and the birth of American truffle farming…

Brandon Flowers: The Killers Inside Me

Ladies Lunch

“Part symposium, part potluck, all pre-mid-life crisis.”CLICK PHOTO FOR FULL ESSAY

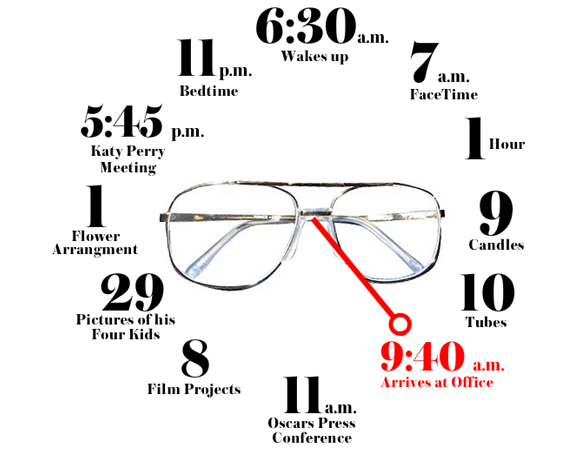

Brian Grazer, A Day In The Life–WSJ Magazine

Oh Captain, My Captain: How Cruise Lines Avoid Blame

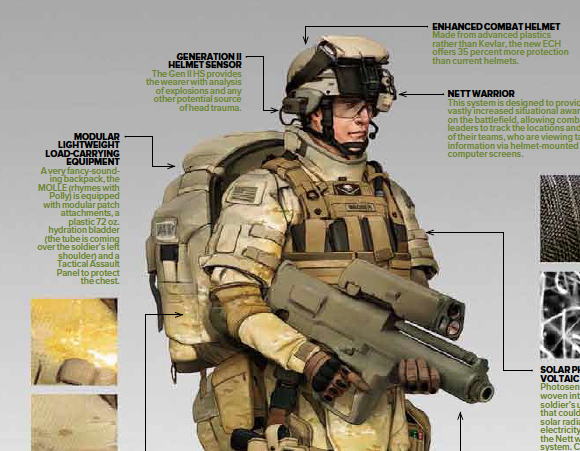

Super Soldiers, Maxim

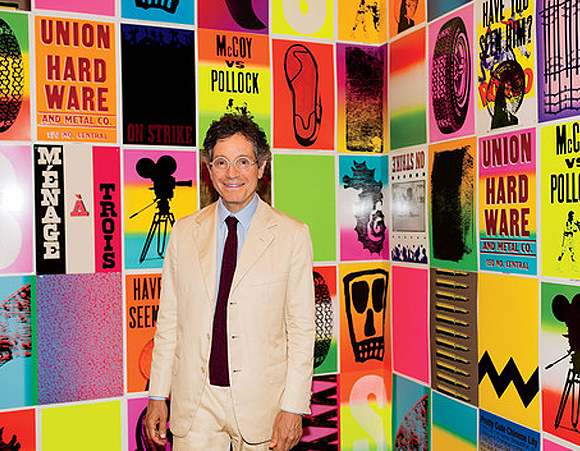

Tracked: Jeffrey Deitch, WSJ Magazine

WSJ Journal Concierge: Seattle

The Roe Less Traveled

click to read Forum Magazine Interview with Stinson Carter

North Louisiana magazine The Forum interviews Stinson Carter about the writer’s life, the Deep South and his novel, False River.

A Novel By Stinson Carter

Click to listen to my interviews on NPR about False River

False River NPR Interview ver. 1

False River NPR Interview ver. 2

click cover to download

on Amazon.com

Watch False River Promo Video below, featuring William Faulkner’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech and painting by Louisiana artist Sam Rigling.

WSJ Adventure & Travel

Sniper School

In the high desert north of Phoenix, 17 men lie prone on a concrete platform behind sniper rifles. Their heavy rounds kick up dust and pockmark the steel targets on a hillside six football fields away. Into this storm of whizzing lead ambles a 10-point buck. Far from the noise of the rifles, he calmly chews on some mesquite leaves.

A shooter yells, “Deer!”

An instructor jumps behind a spotting scope. “Shit, that’s the first one I’ve ever seen out here.”

The shooter’s spotter slaps his partner on the back and studies the majestic stag through his scope. “What a beautiful animal,” he says. “Can we kill it?” click to read

The Favour Of A Reply

The Favour Of A Reply

By Stinson Carter

The invitation came engraved on the finest gilded cardstock. I tried to tuck it away in the pile of bills on my desk, but after ten years of tucking her away, I realized I could no longer keep our past in unopened envelopes and unreturned phone calls.

I was an awkward ex-pat Southerner trying to find my place at a new school in a foreign corner of the country with a grownup secret in my teenage head. And Audrey was the first person I ever told.

After my parents’ divorce in Louisiana, we stopped going to church, I stopped going to private school, and the bank took back the house of my tree forts and Christmas mornings. My father lost his business, my mother lost her fairytale, and I lost any ideas I still had that the grownups can make anything better. My dad ran off to Seattle to build a new life, and my mom and I started over in a Transcendental Meditation community in Iowa. I was twelve. At fourteen, I left my mother and my mantra and moved to Seattle. Six months into living with my father, I found out why our Southern life had fallen apart. He sat me down one afternoon in our apartment, hesitated in putting his hand on my shoulder, and said, “I need to talk to you about the fact that your father is gay.”

click to read full piece

Blood In The Water

Stinson Carter NPR Interview

Air Date: 6/22/10

click to hear my NPR interview on Gulf oil spill

Blood In The Water: We Shouted Out, “Who Killed The Pelicans?” When After All, It Was You and Me.

-By Stinson Carter

The Gulf has always been good to me. I come from a Gulf State, and grew up eating its oysters and shrimp, its Blue Crab and Red Snapper. I fished in it, swam in it, and nearly learned how to surf in it. But I also lived in a house built by oil. Oil paid the bills at my school and filled the coffers at my church. We’re Oil People who love our wildlife, and now we face the grim hazards of that contradiction.

When my mother was eight months pregnant with me, she and my father were swimming at a beach off Destin, Florida, when my mother was taken down by a wave and her plump belly struck the bottom. Hard. They were scared for their unborn son, and even blamed that wave for my premature birth a few weeks later. But I came out fine, and if that wave did me any harm, it was more than made up for by its value as an excuse for bad behavior: “Please forgive me, residual wave damage.” Every year as I grew up, my parents took me back to that same beach to stay in a little rented Florida Panhandle shack we called the Sunshine House. I always used to sprint down to the water the moment we’d end the seven-hour drive to build castles out of sand as soft and white as freshly sifted flour. And at the end of my childhood, when my parents divorced, it was to that same beach that my mother took me one particular weekend when things at home got too hard for her. As the Southern Belle daughter of a Gulf State, there was no landscape more affirming than a white sand ribbon wrapped around endless blue. This was the Gulf that I loved as a child of the Pelican State, and now our Pelican is covered in heavy oil and dying in tar-soaked sand.

But as much as I am the son of a Gulf State, I am also the son of an Oil State. Over water drilling was pioneered a few miles from my hometown, on Caddo Lake, where my grandmother owns stock in a hunting and fishing camp (not to mention, stock in Big Oil). When I was growing up, every house in my neighborhood was built by oil money. In my elementary school if your father wasn’t an Oil Man he was a lawyer who drafted their deals, a banker who handled their money or a doctor who delivered their babies. My father was in advertising, but whenever anyone asked him if he was in the oil business, he’d just say, “We’re all in the oil business.”

Our men love their “Sportsman’s Paradise,” but they also clamor for smaller government with no end in sight; no de-regulation is quite de-regulated enough for their taste. I get emails on a monthly basis from my uncles and cousins in the Louisiana Oil and Gas business about how our president will end the energy sector as we know it, through his government’s meddling. But perhaps what’s really washing up now on the coast is the proof that we can’t have it both ways. Environmental responsibility and industrial safety have never been the path of least resistance for the free market. And this is what happens when we contradict ourselves–wanting Laissez-Faire policies with the oil companies and peel-and-eat shrimp and fresh oysters and pristine places to take our families in the summer time. We have to pick a side: the economy’s or the planet’s, because we clearly haven’t yet figured out how to successfully reconcile the two.

We may be able to cap this hole in the bottom of the Gulf in a matter of weeks. And in a matter of years, we may get our beautiful shoreline back. But how many generations will it take until we shore up our contradictions?

A hole in the ground spewing thousands of barrels of oil a day can be the stuff of dreams or the stuff of nightmares. But the ground doesn’t decide which one it will be; we do.

The Day The Muzak Stopped

In 1990, my father wrote this essay about the closing of Carter Advertising after 13 years. A very, very fine piece of writing.

Cruise Ship Confidential

Lurking below the passenger decks of every cruise ship is a hidden wonderland inhabited by third-world laborers, sex-crazed dancers, nocturnal engineers, and nomadic magicians. Welcome aboard.… click to read full story